Inspiration

Inspiration behind “Anna’s Medallion”

The history of forced labor in Nazi Germany is well-recorded but often forgotten.

Following the German invasions of Austria, Czechoslovakia, Poland, Denmark, Norway, Belgium, Netherlands, Luxemburg, France, Yugoslavia, Greece, and the Soviet Union, the Nazis quickly began forcibly transporting POWs and civilians of those countries to Germany. Once there, the forced laborers were distributed to farms, construction sites, and factories to work without pay and under threat of imprisonment.

Many of the laborers were housed in concentration camps with attached armament factories operated by such firms as IG Farben, Krupp, Siemens, Daimler-Benz, BMW, Volkswagen, Hugo Boss, Mittelwerk GmbH, Gustloff-Werke, and many others. Altogether, approximately 12 million slaves worked in Germany during World War II, from 1939 to 1945. More than half of them perished from exhaustion, malnutrition, disease, hard labor, and Nazi extermination. These men and women came from all over Europe: 3 million from the Soviet Union, 2 million from Poland, 1 million from France, and the rest from seventeen other countries of Europe.

There were twenty concentration camps in Nazi Germany and approximately 1,200 sub-camps. In all the camps, the Nazis’ goal was to extract as much wealth and labor out of the prisoners before killing them in gas chambers or through harsh working conditions.

Some of the camps served primarily as extermination camps, while others were labor camps designed to support the Nazi war machine. While it’s extremely difficult to estimate the total population of the concentration camps due to many records being destroyed just prior to the liberation by the Allied forces, somewhere between 15 and 20 million people were imprisoned in the camps, and 11 to 17 million perished there (including 6 to 7 million Jews).

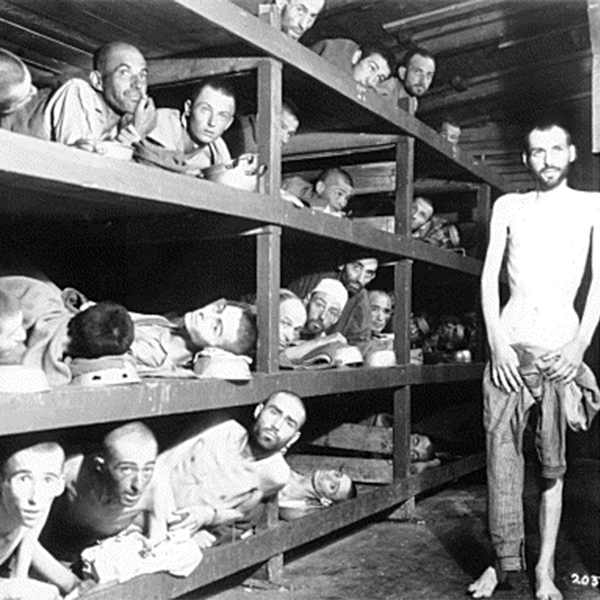

One of the biggest and most brutal labor camps in Germany was at Buchenwald. During its operation, from 1937 to 1945, Buchenwald concentration camp held approximately 239,000 prisoners from various nationalities, including Jews, but also political prisoners, homosexuals, Jehovah’s Witnesses, Roma, and others deemed undesirable by the Nazi regime. It is estimated that at least 35,000 prisoners died in Buchenwald due to harsh conditions, forced labor, medical experiments, executions, and other forms of mistreatment, including starvation and lack of disease control.

While the camp held only 2,900 prisoners initially—mostly communists opposed to the Nazi regime—the population exploded to over 98,000 in the last full year of operation. While Allied forces advanced and the war situation deteriorated for Nazi Germany, Buchenwald’s population surged as prisoners were evacuated from other camps and moved to Buchenwald. Conditions worsened drastically, leading to a high death toll among the inmates.